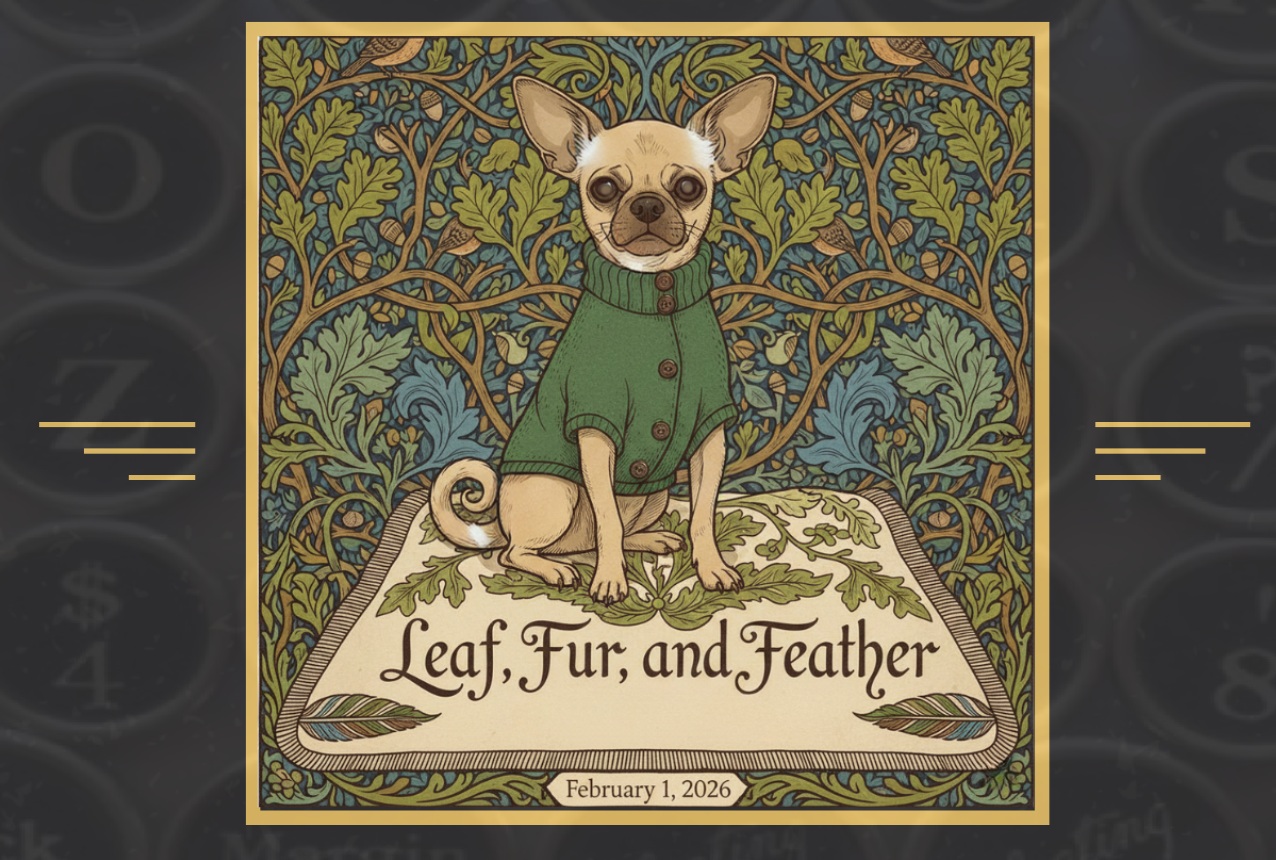

eads turn when the couple come into the restaurant with a round, tannish-whitish, mixed breed dog beside them. He’s a short creature with the stubby nose of a pug and the sculpted cheekbones and sticky-uppy ears of a Chihuahua, with a splash of longish fur in spots across a shorter coat. Imagine a mini pig that had a good roll in horsehair and an issue with static cling, and you have an idea of this dog. On this cold day, he is wearing a grass green handknit sweater, with a row of wooden buttons that jauntily fasten at the neck. eads turn when the couple come into the restaurant with a round, tannish-whitish, mixed breed dog beside them. He’s a short creature with the stubby nose of a pug and the sculpted cheekbones and sticky-uppy ears of a Chihuahua, with a splash of longish fur in spots across a shorter coat. Imagine a mini pig that had a good roll in horsehair and an issue with static cling, and you have an idea of this dog. On this cold day, he is wearing a grass green handknit sweater, with a row of wooden buttons that jauntily fasten at the neck.

He walks easily on a loose leash beside his people. The little dog is clearly blind. The young woman at the host stand is nonplussed when she sees him. Though a sign on the window says Service Dogs Welcome (in handler control), this may be the first one she’s seen come in. She rushes to the manager, who glances at the couple, sees the dog, and smiles. Maybe these guests are regulars, or maybe she recognizes good training when she sees it. She nods to the young woman, who relaxes and plucks two menus from the stand. “Anywhere you like,” she gestures toward tables away from the cold air of the door. I like that she doesn’t try to hide them. It’s lovely that she lets this couple choose. I watch the small dog lift his nose, as though to make sense of the place, and he seems to recognize it. When his people sit, he nimbly navigates past chairs and under the table, where he stands and waits. One of his people has a small blanket he’s expected to lie on, and he knows it. He stands under the table, feels the huff of air and hears the plop of the blanket on the floor, and he settles. Scooting to turn a little, he puts his head on the foot of his partner, the one he serves. Having trained service dogs for fifteen years, of course this boy pings my radar. I don’t want to invade the couple’s privacy, but in periphery, I am watching this dog. He has tucked his back feet under and has one paw extended to touch his partner’s foot. Occasionally lifting his head toward her, unseeing, he has otherwise settled and doesn’t move. He ignores the scrape of chairs and wondering ohhs from nearby patrons. He is out of the way of the waitperson scooting between tables with trays. When a child in a high chair throws a French fry his direction, the dog’s nose works, but he doesn’t move. He seems to register the scent without yielding to it. He is still, quiet, alert. In terms of public deportment, this is an exemplary dog. He is clearly on duty and doing his job. When I get up to leave, I pause beside the couple. “I apologize for interrupting,” I say, “But I train service dogs, and I have to tell you that yours would ace any public stewardship test going.” The woman smiles. The gentleman says, “Oh … thank you so much. He is wonderful, isn’t he? And he gave us that.” He gave us that. It’s a magic thing, a wonderful description of the way some dogs step up and make an extraordinary choice, offering a behavior that communicates or clarifies or supports a need they recognize in another. I’ve had a few of these dogs in my own life. They are a form of grace. They are a gift. The couple want to chat. The man says, “I have no idea how to train a dog, but when my wife got sick …” She smiles and waves her hand. “…he knew it before we did.” “He’s what sent me to the doctor,” she says. She turns to her husband for verification. “Five years …? Five years ago, now.” “We rescued him from the shelter when he was young,” the husband explains. “He’d been there almost a year. He was always blind.” “He is a very good boy,” the woman adds. How he serves his partner is none of my business. Undeniable, though, is how in sync he is with this woman. By touch, by proximity, by scent. Even as the three of us talk, his focus has not shifted to me. I have seen a lot of working dogs, and I’m impressed, impressed with this one. I hope he smells all the feel good chemicals that must be radiating off me in waves, I am so vicariously proud of this dog. “I’ll leave you to your breakfast,” I said. “But I’m so glad to have met you. Thank for all you’ve done for …” “Biscuit,” the woman says. Beneath the table, his brow knits at the sound of his name. The couple beam. “Nice sweater,” I add. “I knitted it,” says the man. “He’s got a gift,” says his wife, bobbing her head toward her husband. Gifts given and received. I leave thinking how much all three seem to have offered each other. Dog and human, they have, in their own ways, made a better life together than they ever would have had apart. © Susannah Charleson, 2026 |